|

|

|

Search our site

Check these out    Do you have an entertaining or useful blog or personal website? If you'd like to see it listed here, send the URL to leon@pawneerock.org. AnnouncementsGive us your Pawnee Rock news, and we'll spread the word. |

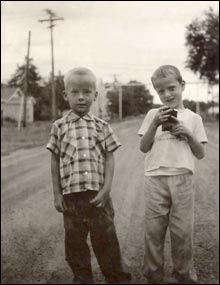

Too Long in the WindWarning: The following contains opinions and ideas. Some memories may be accurate. -- Leon Unruh June 2006Afternoon snacks[June 29] Readers of a certain age may remember one of the Pawnee Rock school's refinements: afternoon sandwiches. We weren't quite at the level of British high tea. Our drink was an 8-ounce carton of milk, and I'm just guessing that we washed our hands first. For lunch on Fridays in the 1960s when we didn't have fish, the cooks would often prepare sandwiches. Steve Ross, who was a few years ahead of me, writes: "If my memory serves me right, we had peanut butter, egg salad and ground-up bologna with mayonnaise in it. I looked forward to Friday lunches and even more to Friday afternoons. About 2:30 or maybe earlier, the lunchroom cooks would bring all the leftover sandwiches around to the classrooms for a nice snack. It was great." For decades I've been haunted by those meat sandwiches. Thinking it was a ham salad, I tried to duplicate the recipe. Now that I've discovered the real ingredients, I'm going to try again. Steve should know what was served. His grandmother, Vida Ross, was one of our cooks. Free to be kids[June 28] Children who run free are the cause of half that's wrong with our city, said a letter to the editor of my big-city newspaper last week. Kids get into things, the letter said. They don't have enough to do, and they're just up to no good.  Wow. It's a wonder you and I turned out OK. You and I grew up when Pawnee Rock kids were tumbleweeds or birds or the wind, or whatever you would call being free to come and go and get into just about anything. In fact, our parents would have felt our foreheads if we didn't get out of the house every chance we had. It was enough to announce, "Mom, I'm riding down to the river with Rob." If you wanted to go play baseball after school or rebuild an engine or bike to the Rock, you just did it. As long as you didn't break a window and were home for supper, everything was fine. Sometimes it's hard to adjust to being a parent in the locked-down world some adults want, and where we live it's not nearly as bad as in, say, Wichita. We want our kids to have the freedom we did, but we want them to be, well, safe. A few years ago it was popular to talk about how "it takes a village to raise a child." Our village raised us pretty well. We knew what was expected of us, and we kids understood that almost everyone in town held us accountable. I imagine that the adults lived by the same rules. It worked because my parents and your parents were related, or they went to the same church and basketball games, or they were in the Lions Club or TOPS together. Our school was big enough for kids to have a variety of friends, and it was small enough for us all to know when something was wrong. Word got around fast in 4-H or Scouts or the lunchroom. I don't want to sugarcoat things. There were some bullies over the years, and a few kids drank and smoked pot and did (or pretended to do) the one thing that was certain to make a reputation. But things balanced out. We ran free, we sometimes didn't have enough to do, and occasionally we were up to no good. But we watched out for one another, and that's why we were safe in our little town along the highway. One tree in the sandhills

[June 27] On the southwest corner of the first intersection east of the Pawnee Rock bridge there lay a sandhills pasture of rough grass. A corral and loading chute stood by the roads, and a few hundred feet inward rose a most beautiful tree. We all have a favorite tree. One cottonwood that grew west of the salt plant intersection was my favorite tree at sunset; its perfect proportions were the perfect counterpoint to the blaze in the sky. I gave a print of it to Dale and Bernadette Unruh for their wedding. Another tree near the Givens home south of Pawnee Rock once struck me as looking like Charles de Gaulle's face. The tree in the pasture stood perhaps 35 feet high and had a well-rounded crown. It stood alone, as if it had been planted there with the idea that one day it would be beautiful. The terrain between it and the road was rolling, gentle dunes of river sand brought from Colorado. And on the ground each spring bloomed gaillardias, or Mexican blanket. Once in a while even a kid from central Kansas can be struck by sheer beauty. It was in my first year of driving to Macksville High School that I saw the tree in its floral setting. I parked my Dodge and stood at the fence for the longest time. The proportions, the colors, the simplicity. Over the years the corral disintegrated in the wind and sun and the tree grew out. But I never drive past this corner without remembering the first time I fell in love with a landscape. Virgil Smith, Pawnee Rock's longtime rural mail carrier and one-time french-horn player, wrote to identify the members of the 1940 Pawnee Rock High School orchestra. Three members later taught school at Pawnee Rock: Mary Louise Hill became second-grade teacher Mrs. Wilhite, Aletha Unruh became kindergarten teacher Mrs. Loving, and Maxlyn Smith became high school teacher Mrs. Schmidt. Power of storms[June 26] Our power went out about 9:30 Sunday night during a heavy rain and stayed gone until midnight. I had been editing a book on the computer, so I took a nap. My wife did the dishes and then sat by the back door reading magazines in the long twilight. The weather left rain at our altitude and lots of mountainside snow 3,000 feet higher. The snow made me think of a storm that blacked out Pawnee Rock in the mid-1960s. That storm was a classic, a blizzard. Pawnee Rockers are used to drifts around snow fences, but this time we could climb a drift to the top of the school shop. And the weather was cold. The snow didn't melt for a week, and power was out for three days. Kids had fun, but I doubt that there was much pleasure for people who worked or who worried about keeping their pipes warm and their kids fed. (One of my favorite photos from the early part of the last century shows a mail carrier working his way through the drifts north of town. You've seen the pictures from back then -- windswept, bare farmland -- and you can imagine how unpleasantly cold and difficult that must have been in the carriages and vehicles of the day.) Weather-related outages were pretty common 30 and 40 years ago -- we lost our lights anytime an ice storm glanced sideways at the city -- but maybe the power grid has been improved since then. In the land of the wind, however, you have to keep your boots handy. Bullhead care and feeding[June 25] Our backyard was like any other in Pawnee Rock. It had a garden, trash barrels, a swingset, and an old refrigerator drawer where I kept fish. Once in a while I'd bring a small bullhead home from Ash Creek and try to raise it to adulthood. Bullheads are bottom dwellers, tough little things, smooth skinned and hard headed and armed with pectoral spines, the perfect catfish for a muddy, sluggish prairie stream. The drawer was, in retrospect, everything a goldfish would love and a bullhead would hate. It was bright and full of clear hose water that didn't stink. I did my best to feed the fish with worms and leftover minnows and crawdads, but it wasn't home. The bullheads, as hardy as they were, usually lasted only a week. When they died, I'd get my hook back. Bullheads are notorious hook swallowers. There must be something in boys and girls that makes us want to tame nature. I was fascinated by all fish, of which bullheads were the easiest to catch and bring home alive. But we all tried to keep frogs and toads. Is there anyone among us who didn't cuddle a baby bird fallen from its nest? I bet you still remember what a jar of june bugs smells like and the yellow-green glow of lightning bugs kept overnight. I suppose it's a joy of childhood to embrace wild things without understanding the power we hold over their lives. With any luck, we grow up with a more sophisticated, kinder understanding of where they fit into our world and where we fit into theirs. All blessings flow[June 23] Before the first spoon dumps carrot salad on a paper plate, before the first hamburger slides off a spatula, before the first scoop of ice cream falls into a bowl, there is the Doxology. Anybody who was in 4-H or attended food-based church functions in Pawnee Rock has the Doxology. I don't know whether anybody ever handed out a songbook and said, "Learn it." It's a combination of melody and lyrics we pick up easily. Even small kids and grown men who fake singing in church can handle the Doxology. You did, didn't you. The verse we know is the last of 12 verses, written by Thomas Ken in the 1670s in England for simple devotions. (I looked it up.) For my money, the first verse is perfect for summer mornings when you get up with the window open and the birds chirping. Awake, my soul, and with the sun Two or three times a year in old Pawnee Rock, we'd have a 4-H meeting and potluck at someone's farm not far from town. Standing by the table, the leader would call for the Doxology, the adults would shush the kids, and we would join the evening meadowlarks. Praise God, from whom all blessings flow; And then it was devil take the hindmost when the food was served. The Sheps The Shep of the early 1950s crowded into this family snapshot with my grandparents Otis and Lena Unruh; their son Elgie, left; their daughter Juletha and son-in-law Herman Fox, center; and the first two Fox daughters, Cynthia and baby Mary. [June 22] Things were much easier when I was growing up. For example, my Unruh grandparents called every one of their series of dogs "Shep." The Sheps were fine dogs. Good rabbit hunters. Swift driveway car chasers. Steadfast lickers of arthritic feet while Grandpa sat in the porch swing. Everything you could want in a farm dog.  Around second grade, I started to want a dog of my own. Grandpa said he'd let me have the current Shep, but she didn't want to go home with me. I found a gunnysack in the shed and somehow got Shep into it. I know, I know. Kids. It's a good thing they're cute, or you'd leave 'em beside the road. Dad and I lifted the squirming bag into the old Chevy pickup and drove home to Pawnee Rock. For about five minutes, Shep belonged to the happiest boy in Barton County. That was long enough for me, and it was long enough for Mom and Dad to agree that Dad should take Shep back to the farm. And that's where Shep stayed for the rest of her days. Shep had several litters of pups over the years, all of which disappeared to other farms or to that place where unwanted farm pets go. But Grandma, who by the mid-1960s was a widow, kept one puppy to be company for Shep and herself. Its name was Puppy, and it lived a long happy life eating Grandma's table scraps and homemade dog biscuits. Water the right way[June 21] Once upon a time, farmers rode combines without air-conditioned cabs. The sons and wives and mothers and daughters who drove the wheat to the elevator or granary didn't have air conditioning, either. The one creature comfort those folks did have was a Coleman jug loaded with well water cooled by ice chunks. Not cubes; chunks. During harvest, Grandma Unruh packed the freezer at night with ice trays, minus those city-slicker dividers that popped out cubes. In the morning, she'd empty the trays onto the counter. Out came the icepick, and soon the jug was ready for the truck ride to the field. It's going to get hot this month in Pawnee Rock. I suggest filling a jug -- Grandma used a mason jar in a pinch -- with real ice water, then going outside to enjoy your drink. If that's not consolation enough, keep in mind that no matter how hot or windy it is, every day from now until December 22 will be a wee bit shorter. So drink up. Happy hour today comes one second sooner. Fizzy memories[June 20] There could be a rut in the old grocery store's wooden floor where I stood at the counter and stared at the shelves of candy, luscious candy. Jawbreakers. Atomic fire balls. Bazooka bubble gum. Bit-O-Honey. Licorice strings. Baby Ruth. That was the time when candy cigarettes were cool in our age group. Who among us didn't pretend to light up the red tip and puff away as we sucked unfiltered sugar? I felt wealthy many times walking past the Christian Church, pouring a Pixy stick down my throat or cracking away on a peanut-buttery Chick-O-Stick. In the winter, my favorite was the Zero Bar, buried in the snow until it was so hard the caramel broke rather than stretched. Drinks were important. Fizzies were Alka-Seltzers for kids. Tab was served in some homes, but I tended toward Cokes or Bubble Up, best enjoyed on my grandparents' porches. Grandma Unruh had an affection for horehound candy, like an oddly addictive after-dinner cough drop. Thank goodness for Thanksgiving and Christmas, when she brought out trays of wavy hard candy. Sometimes the boys ask to see my fillings. Antidote to summer

This is the Larned pool, empty, in January. Swimming in July was no warmer. [June 19] Mark Twain wrote that the coldest winter he ever spent was a summer in San Francisco. The coldest winter I ever spent was 45 minutes last summer in the Larned pool. For months I had been telling the boys about how much fun it was to swim outdoors in the sun. For Sam and Nik, growing up in the north, "swimming" means going indoors to a high school pool and jumping into 86-degree heated water. When we got to Kansas last July, it was a week in the 90s. The boys were keyed up for a leisurely swim in sun-warmed water. Foolish me. I had forgotten my grade-school swim lessons, back in prehistory when the old bathhouse sat at the north end of the pool. Our parents dropped us off to mingle with the Larned kids and headed to Dillon's; we pretended to shower and then gathered in the shallow end. No matter how sunny the day, the water was never pleasant around our skinny little bodies. It's a wonder we learned to do more than float like ice cubes. But I had forgotten that. Instead, I remembered the semitropical water of the summer Arkansas River, and that's the image I promised my boys as we entered the park. We changed our clothes in the bathhouse, practically an open-air building. We rubbed lotion on our untanned skin and stepped off the hot pavement into the water. The boys turned around and wanted to get back in the car. They did spend a few minutes in the pool, mostly because I forced them to. The boys got a swimming lesson, and the lesson hasn't changed: That water's cold. Hunting treasure at the dump

My good friend, the city-dump spinning reel. [June 18] The Pawnee Rock dump, south of the river and east of the O'Rourke bridge, was a fine place for exploring. We took our barrels of burned trash out in Dad's pickup and poured them into the pit, then threw on the branches or newspaper or whatever else we had accumulated in the past month or two. Recycling wasn't an option in central Kansas in the 1960s, but bulldozing everything into a trench dug in the sand was. Then we set about seeing what was new. We're not talking junk, although there was plenty of that. You know what was at the dump -- you may have put it there. Dad once found a handmade metal rocket, its fins painstakingly welded to the foot-high fuselage. I tried everything a fifth-grader could try, but I couldn't get it to launch. Maybe it never was supposed to . . . My prize possession from the dump is a Hawthorne spinning reel. It still works, although these days I keep it on a shelf instead of on a fishing pole. It was crafted of metal in Italy and sold by Montgomery Ward. Over the 20 years of its second life, it brought in catfish, bullheads, carp, white bass, largemouth and smallmouth bass, bluegill and crappie. Thank you, somebody. Occasionally I see photos in the newspaper of children in impoverished nations wading through their city dumps in search of anything to sell or use, and I'm grateful your family and mine weren't in that position. For us it was fun, like a free garage sale. Above all, I think tromping through the trash to find treasure encouraged me to not throw things away too soon. (My wife would like to think this character flaw has a cause, and visits to the dump may be it.) Every one of us is clever enough to find a new or better use for a discarded object or tool, the raw material of homey inventions. Isn't that enough -- a chance to test our wits? Crossings with Dad Elgie Unruh in front of the house he built. [June 16] My dad, Elgie Unruh, likes corny jokes. "Look, the train was just here," he'd tell us kids as we drove over a grade crossing. "It left its tracks." The jokes didn't exactly get old, but they did get predictable. That was part of the fun, part of having a great dad. He is funny and kind, despite a life that sometimes has been pretty hard. Father's Day is just around the corner, and I feel an obligation to write a long piece about the meaning of fatherhood. But the more I try to do that, the more it feels like trying to wrap a house with a roll of aluminum foil. Maybe it's better to simply tell Dad thanks and to tell my sons some stories about him. I'll also probably drive around in my memories. "Dad was just here," I can say. "He left his tracks." Biking across Kansas

My 10-speed Hiawatha, parked in my front yard around 1971. [June 15] When Bill Dirks was a sophomore at Pawnee Rock High School, his every free moment was taken up with dreaming of 10-speed bicycles. Raleigh 10-speeds, and he could show you in the catalog exactly which one he wanted and how he wanted it built. Bill, who was tall and red-haired like Bill Walton, finally got his bike and spent many days riding the paved road near his family's farm -- and beyond. I'm in his debt. I had the good fortune to sit next to him in some class that year, and he taught me a lot about good bikes. It's not as if I knew nothing. Like almost all kids in Pawnee Rock, I had been riding since I was a pup. We kids rode everywhere in that golden age before TV news provided panic attacks every hour on the hour. Up the big hill to the Rock, to school, to the river, to the grocery store. Everywhere. Some kids built their bikes out of spare parts. Stingrays were big then: the banana seat and the upswept handlebars with the little knobby wheels. But I was a skinny-tire kind of guy. Others could do their dirt stunts and pop wheelies; I was going to ride for miles. I started out on a heavy 16-inch bike painted green. Then Mom handed down her black lightweight girl's 24-inch model with a wire basket in front. My next bike, a bronze-colored three-speed 26-incher, was loaded with the kind of goop you put in tires so they will seal themselves after being punctured. (In sixth grade, I took my bike into class during the winter for a science experiment. As the bike stood next to Mrs. Latas, its tires heated up in the warm room and exploded; I don't know whether anyone ever got all the NeverLeak off the blackboard.) Finally I got my first 10-speed, a cheap but sturdy Hiawatha model from Gamble's in Great Bend. My bike and I were inseparable . . . until I landed my first postcollege job and finally joined Bill Dirks on a Raleigh. My brown-painted friend delivered me safely on three-day excursions in the Texas Hill Country -- I rode the same routes as Eric Heiden and Lance Armstrong -- and on an 11-day, 800-mile trip from Austin to Pawnee Rock for Cheryl's wedding. Later, when I moved back to Kansas, it carried me twice on Biking Across Kansas (I met my future wife on one of those trips) and once on a two-day trip on K-14 from Manchester, Oklahoma, to Superior, Nebraska.  When I lived in Wichita, a bike store owner named Al Hicklin let me buy my first dream bike, a neon-blue Italian racing brand named Viner (pronounced Vee-ner). Some weeks, just for the fun of it, I rode 300 or 400 miles. One day, riding with a friend, my 12-speed Viner and I made the Oklahoma-Nebraska run, about 230 miles on that route, in 16.5 hours. See, that's the thing about biking. You can start out rambling around the block and, almost before you know it, you're in Nebraska. A few years ago, I drove to Kansas with our sons' bikes in my truck bed. They got to ride the same sidewalks I did as a kid, rush down the same ditch by the Germans' corner, and parade to the post office. They got to ride as much as they wanted, because you never know when you're young where a bicycle will take you. World War II brought home

The Lightning XP-38 (U.S.), the Koolhoven FK-58 (Netherlands), and the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley (England) [June 14] Kids have always had baseball trading cards. During World War II, they also had airplane cards. Growing up as I did 20 years after the war, I benefited from stuff once thrown in boxes and abandoned in Grandma's upstairs storage room. One of those boxes contained a collection of trading cards. The cards have a color illustration of the plane in flight and a few lines of text on the back describing the plane's highlights. Think of how boys in the early 1940s absorbed the details of planes they heard about on the radio and saw in black-and-white newsreels and newspaper and magazine pages. It worked in the 1960s as well, in that peaceful (for me) period before I saw a newscast of a gunboat heading up a river and discovered that the United States was involved in another war. I was still grappling with the last world war, having some trouble understanding why my people (the Germans) had been at war with my people (the Americans). During the weeks last fall before my dad auctioned off his accumulated stuff, my sister, Cheryl, sorted through boxes and boxes of toys and whatnot and came across these cards and assorted other enjoyments. She mailed a small package of them. You should have seen my sons' eyes light up when they saw the planes. Water and the wind[June 13] They came from Fairbury, Nebraska, and their job was to make the plains livable. Most of them were gone by the 1970s, almost all the rest by the 1980s. They served in solitary duty, beloved mostly by cattle and mud-loving insects.  They were wooden windmills. They stood perhaps 25 feet tall, four long legs lifting the head high into the wind. At the top, the blades fanned out, forced into the wind by the vane behind them. The spinning, usually creaking gears raised and lowered a pipe into the well itself, lifting water out of the aquifer and pouring it into a metal stock tank, in our part of the state often fabricated by Doerr's in Larned. My dad was always after me to photograph the wooden windmills. I suppose he had seen enough wooden artifacts -- wagons and plows among them -- be replaced by soulless metal, and even in the 1970s he felt compelled to preserve at least their memory. This windmill worked in a pasture about five miles southwest of Pawnee Rock, pumping a gallon or two a minute into a tank. A veteran of Pawnee County wind, it was braced at the bottom by a quartet of posts cut from bois d'arc (osage orange), perhaps the hardest of Kansas wood. Newer wooden windmills -- their legs straight and painted white, their braces uneroded by the elements -- still stand at some historical museums. But out where the cattle live, the authentic heroes of the plains are the rarest reminder of the old days. If you see one, take a picture. In fact, take pictures of everything. In 30 years, you'll be glad you did. The song of myself[June 12] Sometimes, it seems, the only thing more patient than the land itself is a grade-school teacher.  Shiela Sutton Smith did her best to bring out the music in us Pawnee Rock grade-schoolers. We sang and danced and played rudimentary instruments during her visits to our classrooms. In fifth grade, I decided that my voice should be deeper than it was, because I wanted to be like the more manly boys. So I forced myself to sing the bass part, even though I was better suited for tenor or even alto, which was normally sung by girls at that age. This went on, I think, for several months. I even growled my way through songs in front of the class. You probably remember those monthly recitals: We stood by Mrs. Schmidt's desk, reading music from a thin hardback book. Some kids enjoyed it. One day in front of the class I just gave up on being a fifth-grade man and sang in my talking voice. "Leon, come here," Mrs. Schmidt said. "I want to shake your hand. That's the best I've ever heard you sing." If you ever thought a kid could float, you could have been thinking of me that day. That little gesture of hers has been a guidepost for me ever since. I don't always achieve the goal, but I know in concrete terms what it feels like. Mrs. Schmidt knew the secret of being a beloved teacher: She made me glad to be myself. Breaker breaker, hang up and drive

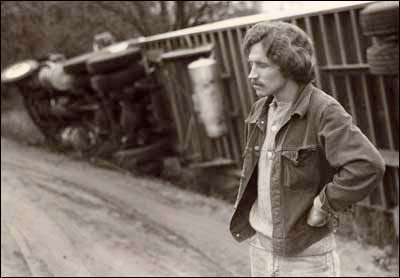

A muddy ditch caused a parked truck to tip over, but the driver's prized possession was safe. [June 11] Don't those drivers with cell phones drive you crazy? Yes, of course they do. Where did they learn to behave like that? I'd say they learned it from us right there on the streets of Pawnee Rock. I took the boys to Blockbuster this afternoon, intending to pick up a couple of good movies. We walked out with, among other things, "Smokey and the Bandit II." I watched it this evening after they went to bed, and I already regret having to tell them tomorrow that the DVD is scratched (it really is) and they can't watch it. I laughed out loud at the visible parts of the movie, but it'll be years before the boys watch it if I'm going to be any kind of good father. The Bandit (Burt Reynolds), as you'll remember, drove a Trans Am fast and used his CB to chat up Jerry Reed and his 18-wheeler buddies to outwit the county mounties. They spoke many of the back-of-the-barnyard terms that you'd hear in any parking lot today; did we talk casually that way 25 years ago? Thirty years ago, I didn't have a citizens band radio in my car, but several of my friends did. They used their CBs endlessly as they zoomed between Pawnee Rock and Great Bend and Larned and Macksville. Geeky coworkers had long talks about "beer cans" and other reception enhancers. C.D. McCall and his "Wolf Creek Pass" were all over the radio. The radios were trusted companions. In 1975 or so, a trucker parked his rig along Janell south of the highway, just northeast of the Lakins' home. It slid into the muddy ditch and turned onto its side. When the driver showed up the next morning, his main concern besides the truck was that somebody would have stolen his "Brownie" -- his CB. You couldn't go anywhere without hearing about the miracle of instant communication between vehicles. You could radio home, you could call the police, you could try to persuade the woman in the car you just passed to give you her handle. Anybody on the same channel could overhear your conversation, but knowing that listeners were lurking was part of the charm; it led to the creation of code words and slang. So, in the end, we ourselves sowed the whirlwind. If teens and young adults today are mindless drivers because they're holding a device in one hand and a steering wheel in the other, maybe it's because they watched their parents worship at the CB altar. Got a 10-4 on that, good buddy? Vacation Bible and batting school[June 9] Most Pawnee Rock kids of a certain age will remember that school didn't really end in May. It was followed by two weeks of vacation Bible school. In our family, that meant five mornings a week at the Bergthal Mennonite Church north of town. Those were great times. All I needed to know about grape Kool-Aid, Popsicle-stick construction, and arranging flannel shapes of biblical figures I learned at vacation Bible school. The best days occurred when we had class under the elms in the shelterbelt south of the church building. The wheat heads were still green, the winds gentle and not overheated. At midmorning came baseball. All the dozen or so guys (I still don't know what the girls did) took to the field for a game during recess. The older guys, such as eighth-graders, batted first. Whoever got a hit went to a base; whoever made an out went to right field, which covered a section of the asphalt road and tall-grass ditch north of the church, and everyone else in the field advanced a position closer to the plate. The pleasant Rev. Gary Stenson was the umpire, and no one argued his calls. In my first year, I struck out every trip to the plate, which was a certain square of the sidewalk between the church and the shed, but I struck out swinging. In my second year, I learned how to take pitches and walked a lot. My glory day was a line drive over the pitcher, who leaped and caught it; it may have been his glory day as well. The fun came from just being part of the game -- having the same chance to hit the hardball as everyone else. In a way, too, the message of our vacation Bible school was that all things are possible if you're in the game. In the late 1960s or early 1970s, the Pawnee Rock churches merged their efforts into a nondenominational Bible school held at the public school. The "romance" of Bible learning was gone; this was just like school. Around the blockSpring tornado season is over, one hopes, but you can dust off your memories by hearing Pawnee Rock's native daughter and columnist Cheryl Unruh read her recent piece about when Emporia was steamrolled by a storm. Listen to "Living in the Alley." Cheryl, who writes a weekly column in the Emporia Gazette, is often asked by Kansas Public Radio to drive to Lawrence and read to the listening public. You can also find wit and wisdom on her website, flyoverpeople.net. The Associated Press wire service sent photos of south-central Kansas wheat around the country Thursday under the file name "bitter harvest." Let's hope wheat around Pawnee Rock is bountiful. A "search" box now appears in the upper left corner of most of PawneeRock.org's pages. I put these on the pages Thursday. The Google search engine isn't fully trained -- it doesn't perform the search of PawneeRock.org as well as it should yet, although it searches the whole web as well as you'd expect Google to. I expect the site search to improve over the next week or so as Google checks out all the pages again. Gas 'n' chat[June 8] As I bought gas the other day at a digital pump under a metal canopy and paid $2.91 a gallon on a credit card, I thought about the Vickers gas station that once stood along the highway in Pawnee Rock. Now, that was a gas station.  It sold gas and oil, of course, but during the 1960s and 1970s it also was the kind of place where a kid with a little money could expect to find all good things of value. I grimace when I think about how sister Cheryl and I pedaled with our nickels to the station every day to see whether a new batch of Monkees trading cards had come in. I'll also admit that I embarrassed our family one day by placing my dollar bill on the counter (I meant business) and asking to buy a set of those plastic bicycle streamers I had seen in a box the day before. They turned out to be the strings of dangling colorful strips that would hang outside the station to attract attention. In the end, my grade-school goofiness was accepted -- or, rather, absorbed. We were all OK at the station. This was no slick dollar-grubbing franchise built on chrome and Formica. The Vickers station was a small frame building, painted red and white, with multiple-pane windows in front and a wooden door that let in a lot of cold air in the winter. What was the attraction? Besides the gas, there was the reach-down 20-cent pop cooler and the frozen-treats cooler. The candy behind the glass wall. The metal chairs, somewhat flexible. The TV, mounted high on the wall near the door to the restroom and always on to the one or two stations that reached Pawnee Rock. The two annual basketball games between Kansas and Kansas State packed a crowd of chat 'n' chew kids and adults into a 12 x 8 lobby. But it seemed that half the guys in town passed through the station every evening no matter what was going on. The station was a kind of oral bulletin board. It was common for someone's last words out the door to be along the lines of "Tell Mom I'm headed home" or "Tell Wilhite to call me." If you wanted to tell Mom yourself, there was a pay phone on a pole a little west of the station. June McFann, who pumped the gas and ran the cash register in the 1970s, practically lived in the station; she and I watched a lot of the summer 1974 Watergate hearings together and I later photographed her for a few hours one November for a college project. Scarf around her ears, she tended cars in the sleet. The station glowed like a cottage in a Thomas Kinkade painting. I think the Levingstons -- Bill, Bonnie and Bo -- owned and ran the place. At some later point, Howard Bowman bought it. Eventually the station was shuttered. But for many years after the high school was closed in 1972, it remained our Pawnee Rock touchstone. Checking the mailJared Smith, writing from Arizona, adds to the list of memorable Pawnee Rock aromas: "Basketball game night in the gym. The smell of popcorn mixed with the varnish on the gym floor." Jared's right on the mark. Wasn't it fun to stand at the stainless steel lunch counter, get your sack of salty butter-flavored popcorn freshly made in the big glass-walled cooker, and take it back to the bleachers? When you were done, you could blow into the bag, choke off the opening, and pop it with an open hand. Speaking of school smells, remember trying to concentrate when Mr. Blackwell or Mr. French was cutting the lawn on a warm day with the windows open? I think we could float on that green scent. And speaking just of green -- when the sky turned green, we headed for Grandma's root cellar, which was rich with a damp deep-in-the-dirt smell. We worried about black widow spiders and the idea that we might come up to an blown-away farm. Is there any other smell that means danger and safety and food all at the same time? Smells, scents, aromas[June 6, part 2] As I watered the lawn one morning this week, the scent of wet dirt and grass rose up and smacked me awake. Think of all the Pawnee Rock memories associated with scents. Here are a few of mine: Summer rimfire[June 6] Women must have some point at which they pass the torch to their daughters and say, "Welcome to the club." For men, that moment might come when they let their son fire a rifle. That's the first point at which the kid holds the means of taking life. And the kid knows it and feels the weight just as much as he feels the heft of the rifle. My first experience with a real firearm -- Rob Bowman's Daisy pellet rifle notwithstanding -- was at the state 4-H camp at Rock Springs. I was about 11 then, and I think I spent half my money at Sergeant Stackhouse's rifle range. I treasured my first targets, and I was as good at shooting as the farm kids were. My main concern was whether I should tell Mom about it. We were a no-guns kind of family, which I didn't mind so much. After all, we were Mennonites and you really could put someone's eye out with those things. Of course I was curious, because a lot of guys drove around Pawnee Rock with guns in their pickup's rear window, the Vietnam War was in the news, and pheasant hunting was as common as fishing. Shotguns and rifles were tucked away in an upstairs room at Grandma's house in the country, and I used to spend hours swinging a percussion-cap 12-gauge across the room and pretending to fire it. Dad had grown up with a .22 and a 28-gauge on the farm northwest of town, and as the Pawnee Rock Township cemetery sexton he used the .22 to hold down the ground squirrel population. (The squirrels' holes made the riding mower tip, and he didn't think families liked the idea of rodents digging around their loved ones' graves.) So, armed with the 4-H camp targets and promises that I'd be really, really careful, I pleaded with Dad for permission to shoot his single-shot, bolt-action rifle. One Sunday evening in the summer, he took me out to Grandma's farm, and he and Grandma set up nylon-web lawn chairs beside the house and watched me punch holes in a target tacked to a board leaning against a bale. My two boxes of shells ran out a couple of hours later; every shot had to be admired. No matter how mature I felt or how accurately I shot, there was never a sweeter moment than when Dad opened the bolt, handed me his rifle, stepped back, and said, "OK, Leon. Hit the target." I went on to use Dad's rifle a lot over the next few years, plugging away at rats and rabbits and stumps and cans and ground squirrels (I was mowing by then too). I became adept at estimating the crosswind's effect on the tiny lead bullet, although I usually came in second when matching wits with jackrabbits. I have several firearms of my own now, although I'm not extravagant. My only shooting in the past few years has been on a rifle range. I still feel Mom looking over my shoulder whenever I stop at a gun counter or admire a friend's collection of guns. In a year or so, I'll buy a BB gun and a package of targets and take our son Sam out to a quiet place in the country. And later, I'll open the bolt on his grandpa's .22, hand it to him, step back, and say, "OK, Sam. Hit the target." If I had a daughter, I'd do the same thing. Land of subtle beauty[June 5] A while back, when I had a job in the Wichita Eagle newsroom, a coworker explained why he had just accepted a job at the paper in San Jose, California. "When I drive an hour from Wichita, I am in Hutchinson," he said. "When I drive an hour from San Jose, I'm in San Francisco." Kevin had found the combination so many of us look for: a good place to work and live that's close to a great place to visit. If Pawnee Rock had a fault -- and I emphasize if -- it's that our hometown is smack in the middle of a region of subtle beauty. The fields of ripening wheat, the sweeping plains, the cottonwoods along the riverbeds, the farmsteads: these are what some city people pay thousands of dollars to vacation amid or to re-create on their ranchettes. For breathtaking scenery, Pawnee Rock's families buckle up for the long ride west to Colorado or southeast to Arkansas or southwest to Big Bend National Park. If my youthful years are an accurate example, our vacationing families stop when we reach the first mountains. Figuring that all mountains look enough alike, we stay awhile then turn for home.  Sometimes, through military service or education or job transfers or just pluck, we get past that first range of mountains and end up in Arizona or Florida or Washington or Alaska. From Pawnee Rock, you can drive four hours and get a fair bit into Oklahoma or Nebraska. You can reach Lawrence or Goodland. But where we live now in mountainous Eagle River, Alaska, four hours puts you at Denali National Park or Kenai Fjords National Park. Even moreso than my friend Kevin in San Jose, we've found a great place to visit that's a great place to live and work. Last week, we took the boys by train north to Fairbanks, in the middle of Alaska, then back down to Denali for a little camping in the Alaska Range. During a drive on the park's only road, in the space of three miles we saw nine snowshoe hares, two moose, four caribou being chased by a grizzly, and a white wolf. I guess the moral is that we don't have to go far to see exciting things, but it doesn't hurt if we do. Sometimes the biggest reward is beyond those first mountains. Pawnee Rock school: $350,000[June 4] Last October, Elgie and Betty Unruh auctioned off their home on Santa Fe Avenue in Pawnee Rock. Dad and his first wife, my mom, had built the place from the ground up in the late 1950s, putting a top floor on what had been a basement house. Dad and Betty decided to give up the place when it no longer fit their needs, which mostly were being closer to medical care and shopping and their friends in Great Bend. Almost all of us go through this crisis of seeing our home taken from us. Dad, for example, was pretty down two decades ago when the farm where he grew up was sold to pay for Grandma's long-term care. And now our town faces the same situation. Our school building/city office building is being auctioned off, for $350,000, amid the garden tools, used DVDs and scrapbooking stamps on eBay. The auction began June 2. Pawnee Rock's early grade and high schools were torn down when they became obsolete. The K-12 building now standing -- and closed by consolidation years ago -- is the first building we've had left to sell. I can't think of another instance in town when something that has belonged to all of us -- in this case, meaning those who went to school there and who now use it as the city building -- has been sold. Even if I don't get to Pawnee Rock as much as I'd like, my old house and our old school mean a lot to me. If nothing else, they are symbols of our youth, of family, of community. Every one of us has our private memories of the school, just as we have memories of our homes. How we felt about other kids, maybe a certain victory in Red Rover or basketball, what we talked about in music class, our daydreams. Certainly, we all hope that what happened in the shelterbelt stays in the shelterbelt. It would be easy to get maudlin about selling the school, but it's something the city council has decided to do. And Pawnee Rock isn't the first town to do it. Our old league partner Bazine has the same idea, as does Lorraine. The school in Jewell was sold and became a hunting lodge; now it's on the market again. In Florence, a former school converted into a home is being sold. What would you do if you bought the school? I have my ideas; you have yours. This, however, is put-up-or-shut-up time. Maybe the eventual buyer will have the best idea of all. I wasn't there for the sale of my childhood home, and I don't know the fellow who bought it. I'm sad for the loss yet glad for the time I had in the house and hopeful that it's being treated well. As for the school building, we'll just have to hope it goes to an imaginative buyer who knows the true value of the Pawnee Rock schools. Shopping list August | July | June | May | April | March Copyright 2006 Leon Unruh |

Sell itAdvertise here to an audience that's already interested in Pawnee Rock: Or tell someone happy birthday. Advertise on PawneeRock.org. |

|

|